This Is Hardcore (album)

Details

- Release date: 30 March 1998

- Label: Island

- Formats: CD, LP (double), cassette

- Recorded: November 1996 to January 1998 (The Townhouse Studios, London & Olympic Studios, London)

- Chart position: 1 (UK)

Credits

-

Writers: Jarvis Cocker, Nick Banks, Candida Doyle, Steve Mackey and Mark Webber

Also: Peter Thomas (This Is Hardcore), Antony Genn (Glory Days) - Producer: Chris Thomas

- Engineer: Pete Lewis

- Assistant engineers: Lorraine Francis and Jay Reynolds

- Programming: Olle Romo, Matthew Vaughan, Magnus Fiennes and Mark Haley

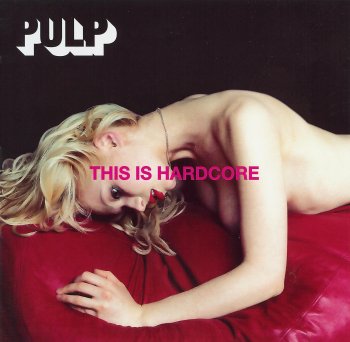

Sleeve credits:

- Sleeve design: Howard Wakefield and Paul Hetherington at The Apartment

- Photography: Horst Diekgerdes

- Art direction: John Currin and Peter Saville

- Casting: Sascha Behrendt

- Styling: Camille Bidault-Waddington

- Model: Ksenia Zlobina

Tracklisting

- The Fear (5:39)

- Dishes (3:30)

- Party Hard (4:00)

- Help the Aged (4:28)

- This Is Hardcore (6:25)

- TV Movie (3:24)

- A Little Soul (3:20)

- I'm a Man (4:59)

- Seductive Barry (8:31)

- Sylvia (5:44)

- Glory Days (4:55)

-

The Day After the Revolution (14:58) (CD only) (5:52) (LP)

Total length (CD): 69:57

Total length (LP): 60:51

Extra tracks on double LP:

- Tomorrow Never Lies (4:47)

- Laughing Boy (3:48)

- The Professional (5:09)

-

This Is Hardcore (End of the Line Remix) (2:59)

Total length (LP): 77:34

Releases

|

Date |

Formats and catalogue numbers |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

30 March 1998 |

CD - CID 8066 Double 12" - ILPSD 8066 Cassette - ICT 8066 |

Original UK release. |

|

30 March 1998 |

CD - 314-524 492-2 |

US release. Extra track:

|

|

30 March 1998 |

CD - PHCR3710 |

Japanese release. Extra tracks:

|

|

14 September 1998 |

CD - CIDD 8066 |

Special UK edition with 'This Is Glastonbury' live bonus disc. More details here. |

|

September 1998 |

CD - PHCR-90713 |

Special Japanese edition with 'This Is Glastonbury' live bonus disc. More details here. Extra tracks:

|

|

11 September 2006 |

CD - 9840048 |

Deluxe edition. Includes a bonus disc of B-sides, demos and rarities. More details here. |

|

May 2009 |

Double 12" - PLAIN131DLP |

Label: Plain Recordings Tracklisting: same as the original release. Heavy 180 gram vinyl. |

Sleeve notes

It's OK to grow up - just as long as you don't grow old. Face it... you are young.

Notes

By manually rewinding the original UK CD by 10 seconds at the very start then letting it play, you can hear the last few seconds of Bar Italia before The Fear starts. On some other versions, such as promos, imports and the deluxe edition, this occurs naturally without the need to rewind.

Reviews

7/10

"There's something to do with realising an ambition," said Jarvis Cocker in the January of 1998, "that seems to curdle somebody's spirit in some way." Curdled spirit. It is a more fitting explanation, certainly, than Millennium Madness or the relentless monsoon rains of the new seriousness that Pulp, three years on from 'Common People' at Glastonbury - The Moment Jarvis has referred to as "the pinnacle of my life" - that Pulp should now choose to bring us their 'Holy Bible'.

Hur hur, just kidding (a bit). But certainly proof of the timeless maxim: that which doesn't kill you makes you stranger. 'This Is Hardcore' is a Pulp LP as you know one only in as much as it's a concept LP about life and the weirdness of everything. It is Pulp: The Sequel. It is the panoramic widescreen director's cut with not one parp on the Stylophone cheese-o-meter or the crackling static from an orgy of Crimplene bedwear, or anything like it. It begins with a drug psychosis confessional called 'The Fear' which sounds like a mock-gothic Hammer House Of Horror theme tune and features a new singing voice as deep and dastardly as Harry White off Mark'n'Lard. "This is the sound of someone losing the plot", he avers, gravely, "you're gonna like it but not a lot". A classic Jarvis jest and one of the very few on an album without lip gloss, razzamatazz or any underwear whatsoever and more a soundtrack to a forthcoming series of Tales Of The Unexpected. With rude bits in.

'This Is Hardcore' is the sound of what happened to Jarvis Cocker when he woke up one day and found life inside The Dream was not as he'd imagined for the best part of a lifetime, a bloke who still stayed in and did the dishes (as pictured here in the jinglesome breeze of 'Dishes') at the same time as playing the international playboy who made a right berk of himself frothing in a puddle outside Brown's being stood on by Keith Allen who mistook him for a plank (or something).

'Party Hard' is the playboy's soundtrack, a bizarre, faintly idiotic 'Scary Monsters' homage full of crisp observation such as, "I've seen you havin' it / Havin' it yeah / But now you've just had it", and furthermore, "why do we have to half kill ourselves just to prove we're alive". In this murky context, 'Help The Aged' finally rises out of the bewilderment mire which deemed it a comeback single with all the fanfare effectiveness of a kazoo. But it's 'A Ring A Ring A Rosie' compared to 'This Is Hardcore' itself, possibly the creepiest single released by a commercial 'artiste' in recording history. Built around a sample of the horn loop from the TV soundtrack of 'Bolero On The Moon Rocks' by the Peter Thomas Sound Orchester (so it's Pulp's 'Bitter Sweet Symphony', sort of), 'This Is Hardcore' is an operatic opus of staggeringly bleak refrain; a paean to a pornographic fantasy as a metaphor for fatal fame. It is spiritually curdled alright; unbearably sad and violently sick. "And that goes in there"... mewls Jarvis, "then that goes in there / Then that goes in there / Then that goes in there". Three million ten-year-olds across Western civilisation in a Tower Records booth simultaneously burst into tears. It is awful. And brilliant. Preposterous, eh?

As is the decision to follow such a feat of emotional dramatics with two namby jingle-pop reveries ('TV Movie' and 'A Little Soul' ) before 'Mis-Shapes' makes a reappearance as an anti-Bloke anthem called 'I'm A Man' and, quite suddenly, the seven veils of gloom begin twitching on top of the burnt-out, broken man on the floor who simply gets up and sings four of the most inspired songs in Pulp's 15-year history. 'Seductive Barry' sounds a bit like Joy Division; that BIG and bewitching, a sexual fantasy space-pop sequence featuring Jarvis objectifying himself in the eye of the beholder, which then turns into Madonna's 'Justify My Love'.

"When the unbelievable object meets the unstoppable force", he coos. "There's nothing you can. do about it, no / I will light your cigarette with a star that has fallen from the sky". Blimey, he's practically floating above the bedspread bathed in blue-and-white light like an apparition of the Virgin Mary (or Frankie Valli in Grease depending on what side of town you grew up on). It could also, of course, describe absolute reality.

The superbly titled 'Sylvia' (hem, hem) sounds, a lot, like the Manic Street Preachers' 'All Surface No Feeling', absolutely ENORMOUS with an idiotic Richey-esque guitar solo and everything (blub), while 'Glory Days' is their greatest urban hymnal since 'Common People' and seems to be, among many other things, about those who live life by the pop star's dictates (and the nutters, perhaps, who thought 'Common People' was all about them). Over an irresistible, rousing jangle the Jarv hollers, "Aw come on... MAKE IT UP YOURSELF! You don't need anybody else..." and you can hear that one, already, beaming back from the future across the hillocks of the summer festivals. Or maybe not. "If you want me", intones the erstwhile voice of a generation, "I'll be sleeping in / Sleeping in throughout these glory days". Magic.

As is 'The Day After The Revolution', the final, mesmerising, ELO-sized soundscape where Jarvis tells us, finally, he's found The Answer: "Why did it seem so difficult to realise the simple truth", he's decided, "the revolution begins and ends with you". Then he stands back, hand at chin, and surveys the preceding chaos with one of those peerless, priceless talky-bit-speeches. "Yeah", he nods, "you made it / Just by the skin of your teeth... The future is over / Sheffield is over / The fear is over / Guilt is over / The breakdown is over / Irony is over / Bah-bye". And so the hardcore life is over, breaking up into a fuzzed-up technotronic bedlam befitting a band who could, at this point, be known as The Space-Pop Radiohead except soaring into space on a 15-minute note of religious ecstasy. Of course it's weird, it's Pulp, int'it?

That the pop folk, at some point, go 'mad' is practically a guarantee. Maybe it's nature's way of telling us human beings are not supposed to be world famous millionaires, sexually beloved by a quarter of a billion. It is madness and sometimes it kills people and sometimes it affords them hitherto untapped dimensions of creative guile. 'This Is Hardcore' grows towards the latter and was built from honesty rather than the 'cred'-bothered, knee-jerk 'success? how vile!' petulance of a 'Blur' or a 'Smack My Bitch Up'. Milkmen's lips may furl less of a morning. Sales of comedy spectacles may plummet. We may have seen the last of the onstage bendy-wrist action 'cos you cannot do that stuff to the new single because it is NOT FUNNY but it is Pulp and is therefore pop and therefore less their 'Holy Bible' and, towards the end, more their 'Everything Must Go'.

Never underestimate the spirit of a man who took 12 years to realise The Dream; he knows, perhaps more than anything, about survival...

(5 stars)

This album is going to cost you about £2,145. That's around 15 quid for the CD itself, then at least £600 for a new, hi-tech hi-fi after your shitty old one explodes after the violent levels of volume you'll be pumping through it Then you've got to consider the fine you'll incur from the environmental health officers sent round by your neighbours (probably about £200) and the wages you'll lose after bunking off work for a week to listen to it solidly (£330, national average). Afterwards, you're still looking at £50 a throw on the 20-odd therapy sessions you're gonna need. And it's worth every penny. Buy two. On every format.

You know you're in for a rough ride the second "The Fear" sets out the album's agenda: "The sound of loneliness turned up to 10". It's the sound of fingernails scraping down a blackboard heart, the panic-stricken screech of brakes this far from that pram, the awful, sobbing howl you hear downstairs when the phone rings too late to be social. This is Pulp's sixth album proper - one short of lucky seven, one past five alive - and it's terrified of something; it's morbid, depressed, paranoid and desperate. And, like anything that falls so low, it's strangely uplifting. As Jarvis cries: "Aren't you happy just to be alive?" on the spiralling, chiming, elegiac "Dishes" and you end up reckoning, "Yeah, I suppose I am. Let's just have some fun, right?"

Wrong. You've been set up for the Duran Duran meets Bryan Ferry rampage of "Party Hard", the amphetamine anxiety when you're too high and too horny just to get your coat and go home alone, the self-disgust that screams: "Why do we have to half kill ourselves just to prove we're alive" Well, because at the end of this party is "Help The Aged" and nobody wants to go there, right? Wrong again.

Although it stumbled arthritically on the radio "Help the Aged" sounds enormous in context, Jarvis' timeless timing taking off on waves of sense and sensibility, sadness, senility and sex. It's pretty dirty, but it's nothing compared to the pornographic title track which follows, with its firm beginning: "You are hardcore, you make me hard", its ripe middle: "It's what men in stained raincoats pay for, but in here it is pure" and its sudden, miserably stale end: "What exactly do you do for an encore?"'' – the post-coital terror of having played out your fantasy and finding there's nothing left to live for.

Musically, it's everything Portishead promised, a swirling cauldron of thick, black sound; magnificently stirring, sickeningly powerful. And that power never fades, from the softly beautiful torch songs, "TV Movie", "A little Soul" and the achingly dynamic "Sylvia", through the driving clamour of "I'm A Man" (every bit as radio-friendly as "Disco 2000" - don't believe the rumours) and out into the premier Human League of "Seductive Barry" – one last stab at finding fulfilment in sex, complete with hypnotically smeared pulses of sound and Jarvis' most convincing whispered, breathless, sighing, panting, urging, vital, needy vocal to date.

All well and good, but there's no "Common People", right? Wrong yet again. "Glory Days" has it all. It's got that ever-rising tune, Jarvis' hollering voice grabbing for higher and higher stars. It's got the same tirelessly sprinting pace, the same euphoric sense of hope and glory and the same sense of sullied justice as Jarvis sneers: "We were brought up on the space race / Now they expect you to clean toilets". He's putting his foot down and he keeps it there with the closing "The Day After The Revolution", an astonishing reprise of the entire album, over-emotional and over-powering. Over the top. Over the worst. Over and out. An incendiary song to end an incendiary album. But ask yourself: can you really afford it?

People's Poet

On the long-awaited sequel to Pulp's breakthrough album, Different Class, England's unofficial laureate Jarvis Cocker perfects his poetry of the prosaic.

8/10

Just before the lights went down at the Radiohead show in London last November, a tall, thin, bespectacled man walked into the arena to take his seat. And a roar went up — or, at least a delighted and genuinely passionate squeal of excitement: "Jarvis! Jarvis is here!" In England right now, the declension goes like this: I love Jarvis, you love Jarvis, he/she/it loves Jarvis, we love Jarvis, they love Jarvis. It is difficult to imagine any other member of Britpop's aristocracy provoking the same reaction — I'm not sure the Gallaghers attract such warmth, and an audience that knows every word of "Creep" probably wouldn't muster much of a greeting for Baby Spice. But then, Jarvis Cocker isn't aristocracy. He's our pal, in much the same way Boy George was our pal: He's pop-star exotic, sure, and he's clearly very smart, but there's something leveling in there too, something representative.

At the beginning of "The Fear," the first song on Pulp's very wonderful new album This Is Hardcore, Cocker sings, "This is the sound of someone losing the plot / Making out that they're okay when they're not / You're gonna like it — but not a lot." It's a lyric that goes some way toward explaining Pulp's appeal in the U.K. For a start, it's resolutely English: The last line is a play on the phrase of an irredeemably uncool game-show host/magician named Paul Daniels, and you wouldn't catch any other pop musician in the entire history of the world even conceding, privately, that Paul Daniels exists. Cocker, however, lives in the same world as the rest of us, and admits as much without sounding too mundane or blowing his chic. That's no mean feat.

The other Jarvis characteristic that explains why people like rather than worship him, is that he is funny — a quality most musicians possess only unwittingly. Now, I've always had a problem with humor in music, mainly because it's invariably hopelessly disposable — how many times do you want to listen to a joke? — but Cocker's wit is capable of gear-changes beyond the reach of most social observers whose currency is the pop song. For a start, Pulp songs almost always contain, somewhere within them, at least a snatch of melody that makes you melt. And, more crucially, Cocker's jokes are always undershot with a kind of benign despair: "Help the Aged" begins with a wry twist ("One time they were just like you / Drinking, smoking, sex, and sniffing glue"), but by the climax — "You can dye your hair, but there's one thing you can't change" — the song is breaking your heart in ways you couldn't possibly have anticipated. On This Is Hardcore, Pulp make it clear they have outgrown Britpop and belong right up there with Ray Davies and Costello and Morrissey, those who look at England with a satirist's eye and a balladeer's heart.

If Cocker does have an eye on rock'n'roll posterity (and if he doesn't, why does the intro to "A Little Soul" pay homage to/rip off Smokey Robinson's "Tracks of My Tears"?), it might explain why the new album sounds slightly clunky in places. The band seems to be aiming for timelessness, both lyrically (there's nothing on this album as au courant as Different Class's rave-inspired "Sorted for E's and Wizz") and sonically, only to wind up sounding a bit dated. Where Different Class paid lip service to modern dance culture, This Is Hardcore occasionally reminds one why nobody listens to new wave albums anymore. In the U.K., new wave was the Boomtown Rats, Joe Jackson, Tom Robinson — mild punk rock with intelligence, sincerity, an organ, and a wearying tendency to write lame songs satirizing the power of the popular press. So it doesn't help that Cocker sounds most like Bob Geldof when he is trying to sound like David Bowie. New wave is a period of British pop that hasn't aged well, perhaps because it aimed for musical neutrality and ended up sounding merely anonymous. After all, what are you supposed to do with music you can't dance or drink to, cry or think about?

Jarvis Cocker is an acute and amusing chronicler of our life and times, and at the moment it is impossible to imagine a day when we will not be interested in his views on more or less anything. But sometimes — on this album's "Seductive Barry" and "Party Hard," for instance — you wish he'd communicate via chat show or letter rather than song. The worst thing music can do — music that has no postmodern intentions, at any rate — is draw attention to its own artifice, and that happens more than once here. It doesn't happen often enough to put anyone off, though, because a good eight of the 12 songs here are as addictive and as cute as pop music can be nowadays. If people love Jarvis, maybe it's because they feel the need for someone like him in their life: Who else is there who smiles back at you in quite the same way? "I'll read a story if it helps you sleep at night / I've got some matches if you ever need a light," he sings on "Dishes," a reluctant redeemer's plea for recognition of his limitations. The irony is, of course, that any performer capable of providing such basic human services is always going to inspire more affection than anybody has a right to expect.

Privates on parade

3/5

The naked and the dead: Jarvis Cocker exposes the loneliness of the serial porn 'n' party freak

"I'm Jonah Jarvis, come to a bad end, very enjoyable."

Dylan Thomas, Under Milk WoodWelcome to personal disintegration - the West End musical. Welcome to an album that amounts to breakdown on Broadway - a situation that makes the above snatch of dialogue almost eerily appropriate. The theatrical source is relevant enough, but the tone fits 'This Is Hardcore' to a 'T' - a man hitting the bottom but relaying the descent with the kind of thespian relish that says he's savouring every last minute of it.

Take your seats then for Twilight Express, the story of a man plotting the desperate limits of his own existence, consumed by porn and left shaken by intimations of his own mortality. Get your tickets now for Lesley Miserables, the tale of a talented Northern rake who gets it all only to find it's worth nothing. The abiding image is unforgettable: Les stands abject and alone contemplating the fall-out from another night's listless hedonism. His face is reflected in a red-lit shop-front, a rivulet of sweat slipping from his brow. The now familiar, "What am I doing here?" suddenly inflates wildly to a more problematic "What am I doing here?" - adrift on this planet and once more seeking oblivion.

'This Is Hardcore' is a remarkable record, an album that takes its narrator's abject decline and relates it with complete frankness. And the Jarvis interview in last month's Select made it abundantly clear that there's precious little separation between these songs and their author. But, if this is a record dealing with breakdown, it has none of rock's traditional dramatic glorification of mental and physical collapse. Instead the ennui, the meaninglessness, the endless melancholy is primped up with a dash of greasepaint, a swelling show-stopping chorus and the sense that, even now, the show must go on.

It's all there in opener 'The Fear', a song that presents "The sound of loneliness turned up to ten" and wheels out time-honoured heroin euphemisms: "A monkey's built a house on your back"; "If you ever get that chimp off your back". At the same time, it's a song which also features the camp aside, "You're gonna like it, but not a lot." Which is 'This Is Hardcore' all over - a record that details bleak, black psychological decay while quoting Paul Daniels, a record that charts ever decreasing circles, while remaining mindful that such was the title of a 1984 sit-com starring Richard Briers.

It's this sense of wry removal that separates 'This Is Hardcore' from the potent heritage of albums that have sent back dispatches from the brink of psychic disintegration. So, unlike Joy Division's 'Closer', Nirvana's 'In Utero' and the Manic Street Preacher's 'The Holy Bible', it seems unlikely that 'This Is Hardcore' will be read posthumously as a final entreaty from someone preparing to depart forever. Which is good news for Jarvis Cocker and good news for the rest of us - because it's clear that Jarvis' achievement on 'This Is Hardcore' is hugely impressive.

In many ways, the album is a telling pop counterblast to the archetypically rock mindsets of 'OK Computer' and 'Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space'. For where those two albums contemplate emotional extremities with solipsistic self-absorption, 'This Is Hardcore' looks at similarly troubling subject matter but always with a knowing look in its eyes and a sense of perspective. There's always the implied wisdom, that, yes, here I am pointlessly wrecked in another small-hours drinking den, but it could be worse - I could be working behind the bar. Which is hardly the kind of humility we've come to expect from Thorn Yorke.

Such lyrical wit and empathy is there in the lovely, bittersweet croon of 'Dishes', a song that has Jarvis contemplating turning 33 (the age at which Jesus died) with typical self-deprecation: "I am not Jesus, though I have the same initials, I am the man who stays home and does the dishes." Such subtlety also runs through the gorgeous, Memphis-tinged father-son confessional of 'A Little Soul' and through 'Help The Aged'. The latter is the song that comes closest to the euphoric spirit of the 'Different Class' album. As with the Manics' 'La Tristessa Durera', it turns the youth-fixated world of the pop song on its head by using it to frame the plight of the OAP. Except, typically of Jarvis' lubricious realm, it concludes that the best way to help the infirm is to give them a shag.

Further testimony to Jarvis' lyrical acuity is the way 'This Is Hardcore' also amounts to a requiem for Britpop. For while Blur signalled the end of that epoch by staging an abrupt stylistic reinvention, Jarvis leads us through a sombre tableau from the end of the party. The use of the utterly jaded, porn-fixated reveller as a metaphor for his own decline also works as a symbol of Britpop's drug-fuelled falling away. It's there in the way the title track details diminishing returns from ever more outré sex acts, but the epitome of this effect is 'Party Hard'. After a vocoder-ed chorus of quite chilling superciliousness ("Baby, you're driving me crazy"), Jarvis says flatly: "I was having a whale of a time until Uncle Psychosis arrived / Why do we have to half kill ourselves just to prove we're alive?"

So, Cocker is in fine lyrical form. What's less certain is the musical content. Because if 'This Is Hardcore' has a distinct tendency toward the stage musical, stylistically it has a suitable fondness for the kind of pastiche and burlesque so beloved of the West End. Such inclinations are there in the way 'Party Hard' sets Jarvis' meditation on joyless good times to a game but ersatz blast of stomping 'Lodger'-period Bowie. They're also writ large in the way the title track corrals John Barry into a shagged-out pornscape, the power ballad-esque chorus of 'Sylvia' and the way Meatloaf can clearly be pictured hamming his way through the lumpen pop-rock of 'Glory Days'.

The fact that the album ends on an optimistic note with the final flourishing chords of 'The Day After The Revolution' ("Yeah, we made it... The Fear is over, guilt is over, Bergerac is over...") just tends to confirm the kind of obvious emotional manipulation you'd more normally expect from Andrew Lloyd Webber. At the same time it has to be admitted that 'After The Revolution' is genuinely affecting in its tugging of the heart strings. It could also be argued that the way that 'This Is Hardcore' takes on limelight aesthetics amounts to a powerful pop-art aesthetic. But even if Jarvis' lyrical valediction does assure that "Cholesterol is over... irony is over" it seems likely that, when the dust settles, this is an album that will seem possessed of just a little too much ironic detachment - in the music at least.

Jarvis' Confessions Of A Pop Singer amount to an startling take on rock-world disintegration, so it's one further irony that it's actually Pulp's music that acts as the height of decadence here - as in the dictionary definition of cultural deterioration following a peak of achievement. Mackey, Banks, Doyle and Webber do retain a charisma, but, too often, this is a band who sound as if they'd be happier doing something else, something far removed from writing a pop song. Certainly, there's little on the album to support Steve Mackey's claims in Select that Pulp have reinvigorated themselves with a more experimental, tech-literate dimension - bar maybe the extended systems music-style outro to 'The Day After The Revolution'.

Who knows, maybe 'This Is Hardcore' will run and run. Starlight Express is, after all, now in its 14th year. But it seems more likely that while 'This Is Hardcore' should be praised as a brilliant, unprecedented lyrical statement, it's not actually one you'll want to play that much.

Velvet Overground

(4 stars)

So, what does it feel like when you've got what you've been waiting for? Fame, respect, a few bob... "Not too good" would have to be the provisional answer, to judge by Pulp mainman Jarvis Cocker's lyrics. In The Fear, the opening track, he introduces "the sound of someone losing the plot". A highly impressive sound too - at the risk of delighting in someone else's misery, or apparent misery since it's all too easy to read confession into Cocker's every word when he's as much storyteller as autobiographer. Either way, as the album progresses, the thought occurs that more musicians should lose the plot, if the results are as fine as these.

If Björk hadn't got there first, the album could have been called Post, post-Britpop, post-celebrity. Pulp used to run a franchise dealing in longing and daydream, in a wish for escape, even - or especially - when Cocker dissected a grubby past and present. Now, since that single (Common People) and that arse wiggle in front of Michael Jackson at the Brits, and two long years after Pulp's last album, Different Class, too much attention has become a concern. "I am not Jesus, although I have the same initials," quips Cocker on Party Hard. Cocker's cute turn of phrase means that Pulp's sound is sometimes overlooked. It's a sound which, more than ever, now slips away from easy definition - the band proving inventive magpies.

With Russell Senior - ex-deputy leader of sorts - now departed, bassist Steve Mackey, Pulp's technophile, might have added a few more loops and fuzzy textures, as on Seductive Barry, an insinuating club come-down, while Party Hard processes Cocker's voice through a vocoder, resulting in a passable impression of 70s David Bowie. But change should not be overplayed. Sylvia comes on like a simple guitar ballad, The Day After The Revolution is Pulp's version of an anthem - that is, anti-anthem - and Help The Aged revisits a favourite trick, Cocker's gentle delivery noting "Funny, how it all falls away", when, of course, it's not too funny at all. This Is Hardcore is Pulp on top form. Which is not to say they feel too well.

Charts and sales

UK Albums Chart

|

Week(s) |

Date(s) |

Position(s) |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

11 April '98 |

1 |

|

2 |

18 April '98 |

7 |

|

3 |

25 April '98 |

12 |

|

4 |

2 May '98 |

21 |

|

5 |

9 May '98 |

20 |

|

6-19 |

16 May - 15 August '98 |

28, 40, 39, 35, 43, 38, 40, 39, 43, 53, 60, 67, 50, 74 |

|

20 (re-entry) |

26 September '98 |

46 |

|

21 |

3 October '98 |

67 |

UK Sales Awards

|

Award |

Copies sold* |

Date |

|---|---|---|

|

Gold |

100,000 |

17 April 98 |

|

Silver |

60,000 |

17 April 98 |

* Awards are based on wholesale rather than retail sales.

US Billboard albums chart

Peak position: 114

Weeks in top 200: 2

Japanese Albums Chart (Oricon)

Peak position: 37